jr / Evolution comes to mind hearing you discuss your practice. Your thought processes are even displayed in how you answer — in length and in depth — so evolution seems to be focal. All studio practitioners evolve (hopefully), but I think this comes to most people over time and without much control. One thing leads to the next and so on. But your descriptions feel evolutionary by concept and practice — like its more of a driving force — like a considered moment from a considered reaction to a considered thought, rather than rushing in to find answers and unveil new questions. These things take time to develop. There is nuance here which allows the visual to fall into place and take hold in a way that rushed, more reactive ways of working might not.

I say this because it is hard not to be reactionary in politics these days. And even though you have had studio/production time, your work sits in real-time and real-space at its core, which could lend itself more toward the reactionary, which might feel less calculated or genuine.

Considering politics, I understand the clear and necessary connection to DDB and your interest in workers rights. I also imagine that growing up under a military dictatorship in Brazil may have helped set the tone for being political. Have you always been political? Where did this instinct and drive come from? How has your relationship and collaborations fueled or hindered your political voice?

NdC / Regarding evolution, I think it really varies from project to project, and to what we are living through at each moment. Some things, especially for me, have become really reactionary in the last few years. I am super influenced and not immune at all to reacting — but overall I think that we particularly react based on our baggage, perhaps like everyone might?

When we are developing a concept, say for instance, ART&COM — which is really not a finite project in itself but a platform for ideas and actions — then if I have some type of more immediate reaction (probably more than Thiago) and throw in a new element in one of the ART&COM “appearances”, it may seem spontaneous and out of place, but it really comes from this repertory that we developed before, either in the same project or even from previous projects.

In Manifesto of the UAAU, 2019 (Collaborative-performance with Thiago, myself and Tracy Collins, with guest dancer Renata Ferreira), I decided to throw in some elements (in particular the handmade protest posters) of Collective Bargain first iteration in 2017 on 14th Street, originally made as part of the Art in Odd Places festival. It was a last-minute decision, an apparent casual use of these elements, but it was in fact very carefully thought. I felt an urge to integrate the audience with us using street protest elements so I threw those posters in their hands — it was a reaction to an urgent need, but also to the time and place of this performance, which was removed from the streets, and had a seated audience. The protest elements were in that moment considered the more developed and carefully considered concepts…

The shorter answer to whether it is planned is that the use or not of reactionary elements might come more from our different training and backgrounds, rather than from a specific theme or immediate time frame. I come from a performance perspective, thus improvisation and the use of objects as a “live” element – sometimes even like “props” – might come easier to me than to Thiago, who expressed to me that some of my uses of these elements sometimes seemed rushed, and I disagreed.

All this to say that the reactionary is also a big part of the picture, although mixed with the more planned that you mention. However, maybe you are right that there’s a driving force underneath it. I have been thinking a lot about that lately — on how this force is the through-line, which ties it all together over the years.

And so that finally brings me to your question: I was 10 or 11 years old when we had the huge street 1980s demonstrations for the end of the military rule and for the return of the direct popular vote in Brazil. Thiago can probably speak more to that, as he participated more, he was about 17. On my side, I may have been influenced by the massive televised demonstrations. Though I really discovered myself politically when I was 13 through Nelson Mandela’s book The struggle is my life in 1986. I followed his last years in prison, his release and the anti-Apartheid movement. That, and the fight against famine in Ethiopia, almost simultaneously, really changed and shaped my view of the world and the omnipresent need to fight against oppression & social injustice.

Everything stems from there for me. Then other involvements in anti-war protests, and with companies like The Living Theatre (much later), co-founding DDB, arriving at Collective Bargain, 2017. Having a political past and nationality in common with Thiago gives us this common vocabulary and language that sometimes, though not always, appears in our collaborations. We also have great discussions daily. It may appear on our individual works too.

As for hindering… hmmm not sure about that, even if Thiago tried…. I am a feminist that reacts quickly, whenever I feel oppressed! [laughs] I actually think Thiago taught me to be a stronger feminist than I was prior to meeting him…

“In the studio we have greater autonomy to take decisions and to shape a body of work. Yet, we also have to consider that the studio is in a concrete building that fits in a particular neighborhood, so in a way artists are also a part of this wider landscape. This landscape is not neutral: it follows a social, political, and economic order that changes with time. …

My artistic and political views are shaped by both the permanent and the changing environment.”

— Thiago Szmrecsányi

Wood, metal, lightbulbs, electrical cords

(In 2019 extended as a collaboration with Tracy Collins, with DMX and programming), Variable dimensions

photo: Marcos Gorgatti

TS / To me, art studios and streets co-exist in time, but they are not necessarily ruled by the same standards. In the studio we have greater autonomy to take decisions and to shape a body of work. Yet, we also have to consider that the studio is in a concrete building that fits in a particular neighborhood, so in a way artists are also a part of this wider landscape. This landscape is not neutral: it follows a social, political, and economic order that changes with time.

As I mentioned before, when I arrived in New York in the late 80’s I was trying to understand the new place, and my previous life in São Paulo served me as a reference. Now my perception is quite different. I have been in the same studio for 26 years and a lot of things around us have changed. My artistic and political views are shaped by staying put and facing the changing environment.

Street, studio, economics, and politics are combined and somehow incorporated into my artwork. In Artivists, 2013, I used lamp shades that come from dumpster diving in the East Village (NYC). The cafe where I worked in the 1980’s had a new owner and it was undergoing a gut renovation in the 2000s. I saw the shades that I used to adjust everyday in the dumpster. I could not let them go, so I took them to my studio where it rested for years. The idea for this sculpture came from those ridiculous yellow wet floor signs that you see collapsing everywhere. They are a warning, though one which is not very stable… I realized that using the shades in the vertical position and introducing a yellow light bulb made them resemble a Constructivism/Suprematism lighthouse. The work is small, the light bulbs are not very powerful, yet it also stands as a warning that now could be well placed on an ideal minimalist loft.

I was puzzled that Artivists came out as a calm and meditative piece at first, so I invited Tracy Collins to bring his input and the sculpture (the lights) became sensitive and responsive to sound. They also respond to chanting, the inner energy of the activists…

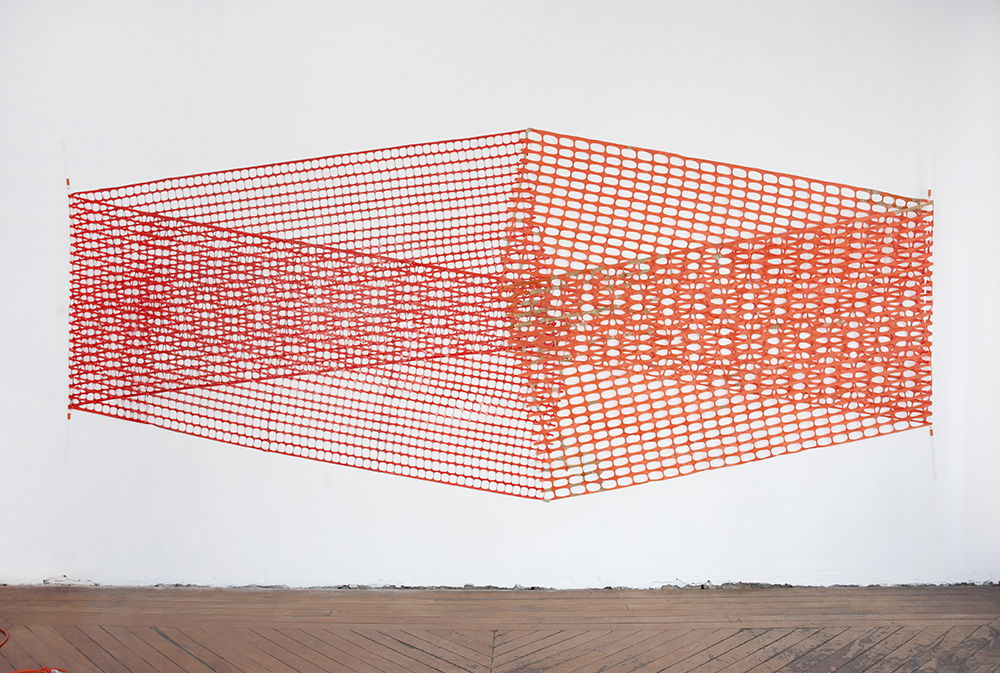

Mesh and Clash, 2014, came from passing everyday through two closed subway stations in Washington Heights on my way to work. They used the barricade plastic mesh to isolate the area and to wrap up materials, and I enjoyed observing how the mesh overlapped. I then obtained the product from construction sites on Delancey Street, and from Atlantic Avenue, on my way between my studio and my home. When I manipulated it, I quickly arrived at this installation that looks like a boxing ring.

I handle, 2013 is a headless giant puppet made out of auto-parts: Ford Van car seats. I enjoy the utilitarian origins of the materials that can be broadly related to workers and to the auto industry. Yet, the title also references the art handling world. One of the most difficult tasks that we have as art handlers is how to deal with the standby moments. Our minds build up too many connections. Some start to complain about the job, some try to promote their own parallel art careers. We somehow vent perhaps due to the loads of commands that we receive, or to the extra care that we have to provide. My giant puppet is a reaction to that. He is on standby mode. He is just hanging out and refuses to deliver his services. He is not handled by anyone else.

Since 2016 I have been on the streets, protesting against the political situation in Brazil. Yet, that has not been the focus of my artwork. The protests do have artistic components, but they are created by a group of people. There many times I follow the lead of others. Collective Bargain departed from us and a combination of these protests, and from ART&COM.

Barricade mesh, packing tape, acrylic sticks, push pins, 85 in. x 178 in. X 2 in.

photo: Marcos Gorgatti